Imprints, Magazines & Presses

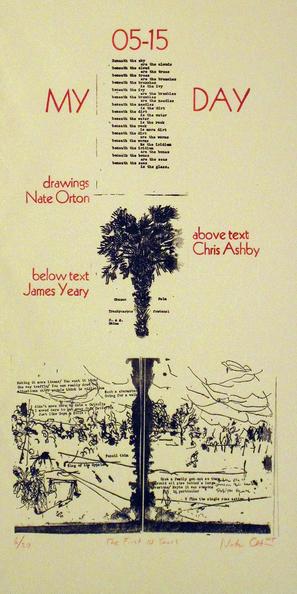

My Day

Nate Orton, Chris Ashby, and James Yeary

Portland, Oregon

2005-

Portland, Oregon

2005-

MY DAY: The First 10 Years (2015)

MY DAY: The First 10 Years (2015)

"In 2004, I moved to Portland to be part of its vibrant arts and music community, but was quickly taken aback by how small and disconnected I felt with my new, and seemingly gigantic city. After a full year I still hadn’t walked down every street. This was a far cry from my hometown of Lewiston, Idaho where I had physically set foot on every square inch of the town. In desperation to ‘get to know’ Portland, I decided to ride The MAX from morning until night. I spent the day drawing in my sketchbook, not an unusual occurrence for me. I turned these drawings into a small book, named it My Day on the MAX, Xeroxed 35 copies, and sold each for a dollar. This tiny artifact proved that I was slowly mapping my new home and slowly becoming part of it. In 2006 longtime friend and writer Chris Ashby moved from Idaho to Portland. Chris and I had collaborated on projects since high school so he was a natural fit to contribute writing and ideas to My Day at the Lloyd Center Mall, then My Day on, under and around the Burnside Bridge. In 2007 another longtime friend, collaborator, and Idahoan named James Yeary moved to Portland. We made My Day at Chopsticks Karaoke Bar on the eve that George Bush announced his plans for a ‘troop surge’ in Iraq. From 2007 to present, output has become more frequent. Most issues include Chris or James, some just me, and My Day Blazers vs. OKC includes all three of us.

"Designating a single day to document a specific place has proven a successful technique for the three of us to express our surroundings in ways that we otherwise couldn't. We only have a day to create an impression; we don't have time to fuck around. For most of the 35 issues, we have stayed true to a physical ‘cut and paste’ method of production. On location I draw with ink in a sketchbook, later Xerox the drawing, cut, then paste onto a master sheet of paper with scissors. Chris and James use notebooks, later they convert text with a typewriter, cut out their text, then paste next to my drawings. Other printing techniques that have been explored are relief, letter-press, polyester lithography, direct typing and crayon-rubbing. With limited aesthetic and mechanical options we are better able to focus on the drawings, writings and construction of the books as well as honor the DIY ethics and aesthetics that the three of us grew up implementing. My Day will continue, here, or elsewhere until issue 100 is completed."

—Nate Orton, June 2015

"The books you mentioned that belong to the so-called ‘mimeograph revolution’ are a great influence on my aesthetic, if because they reinforced that the way I was doing things as a writer-publisher were fine the way they were, raw as fine, or something of the like. My role began with Nate asking me to spend six or more hours with him at a particular place, recording my impressions as poetry, and not revising them. I paraphrase without quotation marks, but I think that was the gist of it. I was already long-interested in Situationism and the idea of psychogeography, though I doubt I had read more than the collection of essays in Guy Debord and the Situationist International and I have a faint recollection of a memoir by RV [Raoul Vaneigem] (whose name I abbreviate because I can't remember it). I don't believe the anthology actually said much about psychogeography, but I remember that there was some reference to its existence, and I do recall being intrigued. I remember trying to seek out psychogeography and coming up with nothing, textually speaking. But I had some idea of the wanderer-artist, and that's something I would hold onto. At the same time, I was reading Walter Benjamin, and the concept of the flâneur went to the same place in my mind, and I think the ideas of the psychogeographer and flâneur went to a dormant part of my psyche, waiting nor Nate to coax them as practitioners of a writing-activity out of me. They really came out in my second MY DAY, walking from Gresham to Mt. Tabor. Over the time that I've been doing this my writing has become more and more invested in understanding my place in these places...my own experience as it interacts with the environments, pushing up against the idea of being a ‘toy science’ constrained by situation but unstructured, a phenomenology of my habitations, and the hinterlands of hometowns. So there's an aesthetic of understanding, or failing to understand, and not trying to prove anything, unfiltered experience that looks out and in at the same time. "

—James Yeary, June 2015

"Designating a single day to document a specific place has proven a successful technique for the three of us to express our surroundings in ways that we otherwise couldn't. We only have a day to create an impression; we don't have time to fuck around. For most of the 35 issues, we have stayed true to a physical ‘cut and paste’ method of production. On location I draw with ink in a sketchbook, later Xerox the drawing, cut, then paste onto a master sheet of paper with scissors. Chris and James use notebooks, later they convert text with a typewriter, cut out their text, then paste next to my drawings. Other printing techniques that have been explored are relief, letter-press, polyester lithography, direct typing and crayon-rubbing. With limited aesthetic and mechanical options we are better able to focus on the drawings, writings and construction of the books as well as honor the DIY ethics and aesthetics that the three of us grew up implementing. My Day will continue, here, or elsewhere until issue 100 is completed."

—Nate Orton, June 2015

"The books you mentioned that belong to the so-called ‘mimeograph revolution’ are a great influence on my aesthetic, if because they reinforced that the way I was doing things as a writer-publisher were fine the way they were, raw as fine, or something of the like. My role began with Nate asking me to spend six or more hours with him at a particular place, recording my impressions as poetry, and not revising them. I paraphrase without quotation marks, but I think that was the gist of it. I was already long-interested in Situationism and the idea of psychogeography, though I doubt I had read more than the collection of essays in Guy Debord and the Situationist International and I have a faint recollection of a memoir by RV [Raoul Vaneigem] (whose name I abbreviate because I can't remember it). I don't believe the anthology actually said much about psychogeography, but I remember that there was some reference to its existence, and I do recall being intrigued. I remember trying to seek out psychogeography and coming up with nothing, textually speaking. But I had some idea of the wanderer-artist, and that's something I would hold onto. At the same time, I was reading Walter Benjamin, and the concept of the flâneur went to the same place in my mind, and I think the ideas of the psychogeographer and flâneur went to a dormant part of my psyche, waiting nor Nate to coax them as practitioners of a writing-activity out of me. They really came out in my second MY DAY, walking from Gresham to Mt. Tabor. Over the time that I've been doing this my writing has become more and more invested in understanding my place in these places...my own experience as it interacts with the environments, pushing up against the idea of being a ‘toy science’ constrained by situation but unstructured, a phenomenology of my habitations, and the hinterlands of hometowns. So there's an aesthetic of understanding, or failing to understand, and not trying to prove anything, unfiltered experience that looks out and in at the same time. "

—James Yeary, June 2015